James Bond and Fragile Masculinity

I don't know how complainers would cope if they knew the British secret services routinely employs women as field agents, and have done so for over a century. Make them cry harder? Though moaning about women replacing male characters in popular culture is nothing new, we've come to see more of it lately. In fact, it appears to be accelerating. Star Trek Discovery got it in the neck for daring to cast a black woman as the lead character, a few years ago the Ghostbusters reboot received brickbats not for its quality, but because it starred women. As I write there's another meltdown happening because Natalie Portman is due to play Thor in the next cinematic outing for the character (never mind "female Thor" has already featured in a run of comics). It is certainly true we are seeing a greater visibility of women in more varied TV and film roles, and this has especially been the case this last decade with dozens of acclaimed woman-led dramas getting the plaudits and reaping success. So pushback was inevitable. But what is the root of this? Why should the masculinity of some men feel affronted when fictional characters have their genders flipped? Why the abject failure to man up?

It speaks to a certain anxiety in the world. The so-called alt-right with its performative displays of misogyny, such as the desperately try hard sexism of failed UKIP candidate, Carl Benjamin, is a symptom of gendered entitlements in crisis. Indeed, the incels, the Men Going Their Own Way movement, the "perfect gentlemen" who gun down young women, the popularity of Jordan Peterson's self-help manuals, the attraction - to some - of fascism, belies a certain frustration. The gendered codes curled up in our socialisation, and force fed us through multiple streams of media still assume male supremacy. It is the unremarked, unspoken starting point for so much. It assumes men are individuals who acquire their manly status by asserting themselves against the world. Women on the other hand are defined by their relationships and responsibilities toward others, they are part of the world to be asserted against. The problem is that while gendered inequality obviously still exists, and men have the most wealth, the most opportunities, and are therefore more likely to possess the above entitled mindset, the relationships underpinning this are shifting quickly. And decaying.

A lot of this has to do with work. For as long as the bulk of the population have to sell their labour in return for a wage or a salary, class matters, and the forms it takes shape and condition gendered expectations and experiences. The industrial worker, once the hegemonic form of conceiving and being working class (and still is for some centrist-types), dominated the 20th century. Manual work, toil, sweat, dirt, the physicality of working the land, in a factory, or an extractive industry ensured class markers were simultaneously gender markers. Coupled to this elision of strength and manliness were the ideologies associated with the social wage: men were responsible for providing for their wives and families, and the understanding - the tacit social contract between labour movement, the employers, and the state - was the wage provided for all the family. Men then were providers, and as the sole or main income their wages were the material basis for patriarchy at home. However, male dominance is not preordained. Since the 1970s, the social wage has declined and with it more women have entered into the work force; the masculine industries of old have undergone steep decline, meaning these kinds of jobs are increasingly things of the part; men and women increasingly compete for the same kind of jobs. And lastly, the character of new jobs are a lot different from the industrial worker of old. And so as the grounds shift, proletarian patriarchy is destabilised.

These new jobs, characterised by immaterial labour are based around the production of knowledge, services, care, relationships. These do not the use of the body's brute force but our social capacities and aptitudes - intelligence, creativity, empathy - and these are mobilised to make relationships, and profits. This highlights an interesting tension in the way contemporary capitalism works. The individuated masculinity of the industrial worker has been recouped and redeployed culturally, and as a mode of governance in the age of neoliberal capitalism. We are posited as individuals who are, fundamentally, on our own. Gender, ethnicity, sexuality and background are no longer barriers to success. You get out of our meritocratic systems what you put in. You, the individual, is sovereign in ways the masculine classed subject used to be. But there is a glaring cultural contradiction between this consumerist sovereignty and having to submit to the will of others in the workplace, be it the employer directly or the demands of service users and clients. This is where masculinity has particular difficulties. The continuities between masculine and neoliberal subjects renders men at a double disadvantage in job roles fundamentally oriented toward others, whereas these same jobs are culturally more attuned to feminine virtues. Cooperation, networking, caring, empathising, all the facets of emotional labour draw upon and have greater fit with the gender socialised into these mores. Therefore men are more likely to suffer a gendered form of anxiety between their gendered and classed positions, and in a very real sense are at a competitive disadvantage as these kinds of jobs and careers grow - for as long as the gendering of boys and men does not keep up with developments.

What this means is we have a man's world in the process of becoming something else. The sexism of the age of industry was about maintaining separation, of reinforcing a sexual division of labour around highly gendered modes of work. The sexism we see today recalls past privilege, but is fundamentally rooted in relationships in long-term decline. It comes from anomie, of men raised and habituated to a world that only partly exists and is fading rapidly. And so we see a recrudescence of violence against women, of shock value sexism, and the incessant whining about women ruining video games and films. They know the game is up and their privilege is slipping away, and we're left with a dwindling band who were promised the earth, but all they got was a shitty bedroom and a chip on their shoulder.

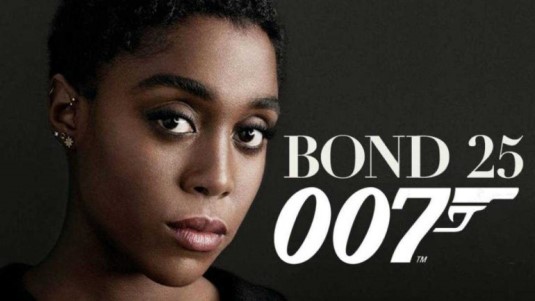

And so whether it's James Bond, Thor, Star Trek, Ghostbusters, or something else, we're going to have to suffer the wailing voices of dethroned masculinity until the point they dwindle into irrelevance. It might be unpleasant, it might be damaging, but as night follows day they are destined to be crushed under the weight of the fates. Male privilege is under attack, and its survival isn't looking good.

Comments

Post a Comment